|

Most people know something of Bryan Blundell, and how he

was moved by the plight of children roaming the streets of Liverpool, starving

and destitute, that he founded The Blue Coat School in 1715 and dedicated the

rest of his life to its cause. Two centuries later in the early years of the twentieth

century such children were the ultimate concern of Jessie Crosbie, a leading

educationalist and pioneer of child welfare practices and home-school links. For

more than thirty years she was connected with Salisbury Street Council School,

Islington, of which she was headmistress. It is said that she always taught 4Rs

‘Reading, Riting, Rithmatic and Respect’. Miss Crosbie taught in the Childwall area for several years before moving to the small Salisbury Street school in Everton and soon realised how different the two districts were. As she got to know the children and their families she was shocked to find out how poverty stricken the community was. In her autobiography * she wrote that it was no good trying to teach children who

‘had no food in their bellies. Many came to school on cold winter

mornings Talking to the children she learnt that many had no beds at

all, only old mattresses or old coats on the floor and they regularly roamed the

streets until after midnight. Jessie was determined to see that the children had at least

one meal a day at school. She visited local shopkeepers and, mainly through

their wives, persuaded them to donate food. Soon a supply of bread, jam, milk

and cheese came into the school for the children. When butchers and greengrocers

were targeted by Jessie, she managed to acquire; vegetables, cheap meat and

bones, providing a hot meal at midday. The Council’s School Meals Service was

based on Jessie’s scheme. The next problem she tackled was local children roaming the streets at night. Miss Crosbie contacted Father Dukes of St Francis Xavier’s Church, who also expressed concern about the problem of juvenile delinquency, which existed throughout the area. Between them, they initiated a plan to deal with the situation. They would set up a curfew. First a Play Centre was set up at Salisbury Street School which opened at 5 o’clock every evening, and every pupil was expected to attend. All the Catholic children were ordered to attend Benediction every evening at St Francis Xavier’s church. Then, at 7.30pm Father Dukes led the children out of the church and Miss Crosbie led her children out of the school and helped by the teachers from both schools, each child was taken home. Any odd truants spotted on the way, were collected, and escorted home as well. A group of parents was organised into a patrolling the streets until the pubs closed to see that no children came out again. Miss Crosbie and Father Dukes maintained this Curfew for many years. The Play Centre at the school was, like the School Meal

Service, were the first in the country. The scheme was officially adopted, first

locally, then nationwide in the Thirties and continued successfully for many

years. Jessie Crosbie also introduced the first nursery school in the country

and the first parent-teachers organisation. She had baths installed at the school at a time when hardly

any houses in the district had bathrooms and the children were persuaded to use

them. Mothers were invited to bring their young children in to bath and arrange

for the little ones to be looked after, while the mothers had a bath themselves

or did their washing in the basement sinks. During her years at the school it held record for the

number of scholarships awarded in the city. There had been none before she came.

Besides their educational needs, Miss Crosbie concerned herself with the

personal welfare of the children in her charge and involved parents in

discussions on tackling problems related to home and school. She never married and was awarded the MBE in 1933 for her

contributions to educational practices and in 1842 received an honorary M.A.

from the University of Liverpool. After retiring she travelled the country,

lecturing on education and wrote many articles. She was a revolutionary, ahead

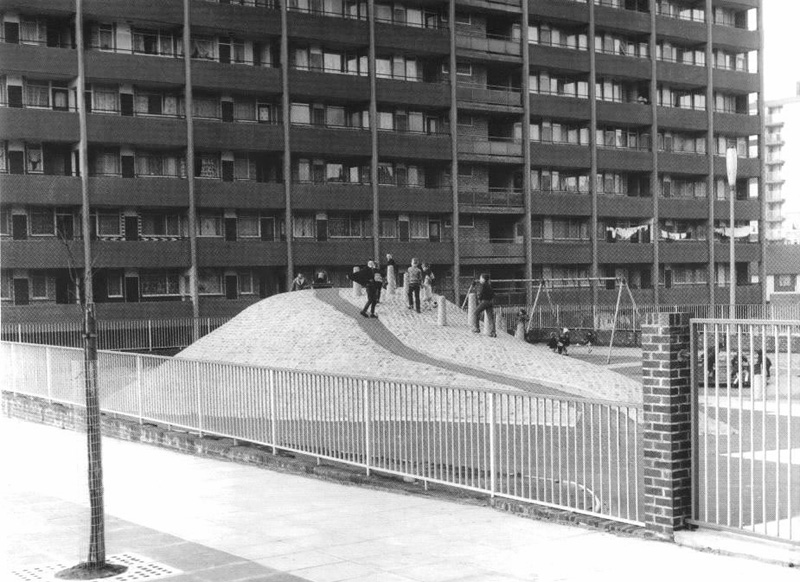

of her time, seeing many of her ideas and schemes adopted nationally. In 1961 she was knocked down while crossing the road and was taken to Stanley Hospital and later Southport Nursing Home where she died the following year. The school and houses in the area were demolished in slum clearance sometime ago and blocks of ‘high rise’ flats were built on the site. The only Memorial to this remarkable women, was the naming of one of the blocks ‘Crosbie Heights’ and this was at the insistence of local residents. The flats have now made way for a modern estate of houses of which Jessie would have approved. * ‘This Kingdom Called Home’ by Jessie Crosbie © Joyce Culling 2005 There is more information about Jessie Crosbie at the

Museum of Liverpool Life web site:

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/liverpoollife/life/displaylife.asp?id=15 There you will also see:

Crosbie Heights Also see Mothers of the

City by Michael Kelly |